8. Epilogue

Admiration for Certain Groups of Dutch Artists

Now we will try to define the Dutch influence on German art in a short overview. Is it not striking, that so many Dutch artists found employment and earnings in Germany, while many German talents left their country due to a lack of both?1 Many are listed at the beginning of this section. At the time, the Dutch culture of painting was far superior to local art in Germany. Therefore the foreign was so much in demand, particularly at the courts, where Dutch portrait painters were primarily employed. We only have to recall the conditions in Brandenburg-Prussia, to grasp the significance of these portrait painters. Local artists were only good enough to make copies that could be sent to an artist in Holland to be engraved.

Generally speaking, Dutch-German court art only began to develop at the end of the 17th century. Consequently, one admired not the ‘true’ Dutch art, but its highly overrated aftermath.2 The activity of artists for the Düsseldorf court under Johann Wilhelm is the best example of painting at this time of decline, that triumphed in Germany.

It is hardly surprising that painting in Northern Germany, especially in Hamburg, was very close to Dutch painting, not only in portraiture, but also in genre paintings, still-life, landscape and marine painting, in short: in everything, even more so because Dutch art also was to the fore in the Scandinavian countries. That a Dutch, bourgeois painting culture developed in Frankfurt, Nuremberg and even in Augsburg, was not to be expected, and even less that this would maintain next to the Southern-German, Italian attuned style used in large altar pieces.

What was actually admired in Dutch art? Which artists came over and which artworks were in demand? This varies between regions and times. Mannerist compositions were evenly disseminated in the whole of Germany, but this was before the period of the actual Dutch influence. Initially, the Berlin court was simply attracted to the Dutch Realism in portraiture. Out of the same desire landscape artists were sent for in order to record the electorate estates; even still-life painters were attracted to the court to immortalize rare formations of plants. Realism in still-life led to the popular trompe-l’oeil representations that amazed everyone.3 Allegories and allegorical glorifications soon followed, for which suitable artists could be found in Holland as well. This went hand in hand with a more refined, elegant pictorial language (Wallerant Vailliant) and a yearning for decorative painting (Augustinus Terwesten). In the Palatine, on the other hand, Dutch Feinmalerei [fine painting] was adored above all (Eglon van de Neer, Adriaen van der Werff), which certainly is a Dutch genre, but just one out of many others.4

In non-courtly circles, i.e. the bourgeoisie, most types of Dutch painting were appreciated: marines, still-life, battle scenes (Philips Wouwerman) and daily life genre painting (Wolfgang Heimbach). At the time there was no understanding of great Dutch landscape painting, from Jan van Goyen to Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema. More often, on the other hand, one comes across landscapes by Jan Both, Nicolaes Berchem and Pieter van Laer in old collections, as well as Herman Saftleven and Jan Griffier, who soon found their German imitators.

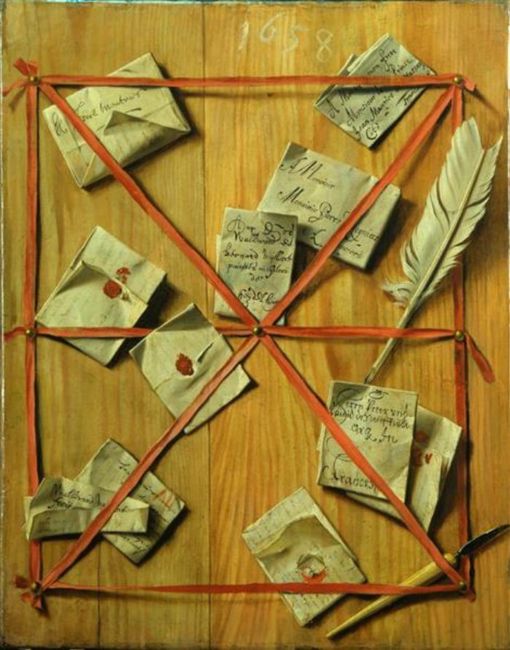

Cover image

Wallerant Vaillant

Letter rack with letters, dated 1658

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv./cat.nr. 1232

Response to Other Theories

What was known in Germany about the art of Rembrandt? There was no lack of German artists who studied his work in Amsterdam: Jürgen Ovens, Johann Ulrich Mayr, Michael Willmann, Joachim von Sandrart I, Christopher Paudiss and others.5 Nothing of the master’s expressive power and of the calm, classic style of his later works passed on to their works. Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro remained with them for a while, as well as the soft, painterly modelling (Paudiss) that distinguishes the Rembrandt school as a whole. Willmann, Mayr and Sandrart soon had to adjust to the wishes of their patrons of large altar pieces and possibly also in the iconography of the image type, that to a great extent was determined by Rubens and the Italian artists. Jürgen Ovens was an eclecticist, which was no disgrace at the time. Christopher Paudiss, who remained true to his master’s style the longest time, was not very productive at all.6 This way only a fraction of Rembrandt’s late style was carried into Germany by his pupils. It was, so to speak, only a faint reflection of a brightly shining comet.

This recognition is not the merit of our research: it can be found in many old handbooks.7 In more recent German publications other conclusions are drawn. However, these are not based so much on new observations, but on theories that up to now were unfamiliar in art history. We leave it to the reader to address these in detail. Only one characteristic example has to be singled out here.8

Nobody will deny that German art of the 17th century also had its own character and was not simply a poor imitation of Dutch, Flemish, Italian or any other art. In a publication that does not have the primary purpose of dealing with the influence of Dutch art, it would be possible to present the particular German characteristics in a more detailed and kinder fashion than is the case here. On the other hand, the same authors claim that the Germans of the 17th century, as a people related to the Dutch, were particularly sensitive to Dutch influence, implicitly admitting a dominance of non-Germans. One even goes a step further in the happy recognition of a kinship and speaks of a Low German realm from Bruges to Königsberg as a cultural unity with interactions since the days of Jan van Eyck and earlier: the ‘secretly vivid circulation of Low German art production’9 only became visible to the modern and well-trained (or prejudiced?) observer. We leave aside the comparisons adduced as evidence, from the Naumburg Master until Jan van Eyck, that are completely outside our subject, and limit ourselves to the 17th century, the ‘Golden Age’ of Holland. First of all, we have to separate the painterly cultures of Flanders and Holland, that were clearly distinguished at this time, despite of the interactions.10 Although we often regretted not to be in the position to deal with Netherlandish influence as simultaneously outgoing trends from Holland and Flanders in the course of our research, this restriction kept us from treating the two politically different territories as an entity. When we lump them both together with North German art and present the mix as Low German art, one can surely -- yes, why not? -- discern ‘secret’ interactions, but a sceptic or a prejudiced observer will not be convinced of the homogeneity nor of the interactions of this creation.

In truth, when we review German artists like Wolfgang Heimbach, Mattias Scheits, Jürgen Ovens, Govert Flinck, Michael Willmann, Christopher Paudiss and the rest of them, and reflect once again on their life journey in Holland and Germany, there is only one conclusion: one cannot speak of interaction in that time. On the contrary, it is striking that these young Germans started to flourish as soon as they came to Amsterdam. Artistic impressions of all kinds encouraged them to make artworks that one would search for in vain, had they not shaken off the dust of their homeland from their shoes. The painterly cultivation they achieve in Amsterdam is the peak of their creativity. But too often they wither away again in the German province. This is hardly surprising. Many of their Dutch colleagues that were respectable painters in their homeland, also lost the footing they needed to create something good. Unusual wishes of their patrons did the rest to undermine their sense of style. Not every capable Dutch or Dutch-trained artist was able to paint singularly impressive allegories and festive decorations for a German prince, or radiantly religious altar pieces for churches and cloisters. Flemish artists were more successful in this, but does that therefore mean that their works were more ‘German’ than the dim, more or less dry, but all the same loyal reminiscences of the German Rembrandt pupils?

This delusion indeed is advocated by some young theoreticians, since allegedly ‘the German nature with its mystic-irrational view of yearning for its very own soul evolvement, corresponds more to the Flemish being than to the sober, anti-romantic and rational Dutch character’.11 Others are indulging in the assertion that ‘the German spirit gathered and pondered in painting of the 17th century, which was only expressed by the Dutch and ̶ slightly restrained ̶ by the Flemings’.12 The state of the German spirit is really not so poor that is has to reveal itself in the guise of another culture. In view of such intellectual derailments it is probably not superfluous to repeat here the warning words of a competent German art historian: ‘Does Germany really need to simply claim Rembrandt and the Dutch painters of the 17th century as German?’ Yes, here the actual problem for the German art historians arises: ‘Why have Rembrandt and the Dutch 17th century not emerged here at home?’13

Notes

1 [Van Leeuwen 2017] Tacke refutes the latter; German artists mostly travelled mostly abroad during their Wanderjahre (Tacke 1997, esp. p. 52-54). Dutch artists only were in more in demand at the courts, not in the towns.

2 [Van Leeuwen 2017] This 'highly overrated aftermath' recently has raised interest in art history: Aono 2015.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] An unknown B. Pfaffenhoffen also painted such pieces (photo Witt Library). [Van Leeuwen 2017] Identical to Simon Georges Pfaff (1715-1784) (Baron Pfaffenhoffen). The gouache drawing is in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery, London (RKDimages 285282).

4 [Van Leeuwen 2017] Sluijter et al. 1988.

5 [Van Leeuwen 2017] Heinrich Jansen, Gottfried Kneller, Johann Ulrich Mayr, Christoph Paudiss and Franz Wulfhagen are the only documented apprentices of Rembrandt. Houbraken mentions that Ovens was a pupil of Rembrandt. However, stylistically there is little influence of Rembrandt to be found in his work and there is no other source to corroborate Houbraken's unsubstantiated remark. Michael Willmann was in Amsterdam c. 1650, where he got to know works by Rembrandt. In literature on Willmann it is often stated that he could not afford to become a pupil in the workshop of a Dutch master. Naturally Joachim Sandrart, who was Rembrandt’s age, was not his pupil, but he did admire Rembrandt (Sluijter 2016).

6 [Van Leeuwen 2017] For the Gerson project all 106 artworks known to us by or attributed to Paudiss were entered in RKD Explore by Tess Zitman, bachelor trainee of Leiden University.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] W. Bode speaks about German painting in this period as a ‘most unedifying chapter’ (Bode 1891, p. 167).

8 [Gerson 1942/1983] Konrad 1937; the rejecting review on Konrad 1937 in Geyl 1938, p. 192. A repetition of the theory of Konrad in R.P Oszwald in Das Reich 1940, no. 3.

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Konrad 1937, p. 118: ‘Im Verborgenen lebendige Kreislauf niederdeutschen Kunstshaffens’.

10 [Van Leeuwen 2017] Gerson refers to the first chapter in his book on Dutch-Flemish interrelations (Gerson 1942/1983, p. 7-38). On Gerson's idea's on the correlation between Dutch and Flemish art: Van Leeuwen in Gerson/Van Leeuwen/Tylicki et al. 2013/2014, § 2.1.

11 [Gerson 1942/1983] Neustein 1935. The bold claim that Caspar Netscher (!) marks the highlight of Dutch-German artistic influence, is typical for the absurdity of the rest of the examples.

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Grunewald 1929, p. 7. Rembrandt, Jan van Eyck and Albert van Ouwater are all considered as being German artists.

13 [Gerson 1942/1983] Pinder 1933, p. 406: ‘Warum nun eben doch Rembrandt und das holländische 17. Jahrhundert nichts bei uns selbst enstanden sind’.